July 2020

Kieran Maguire looks at how one top football club, Derby County, changed its accounting practices to make things look better off the pitch.

Derby County Football Club was incorporated in 1896. It has

detailed the accounts of this fine club ever since. Anyone who

has been to Derby for a match will tell you it has traditionally been

a great day out for away fans, either at their former home, the Baseball Ground, or at Pride Park, where locals call everyone “duck”, which is endearing if a little odd. In September 2015 Derby County Football Club Limited were acquired by SevCo 5112 Limited, a company set up by local businessman Mel Morris when he bought the club from its previous owners.

SevCo 5112 Limited’s accounts for the first year of trading were

for the 12 months to 31 August 2016, which is perfectly acceptable. It did mean that including the results for Derby County Football Club Limited was a bit tricky, as Derby’s accounts were to the year ended 30 June 2016.

Under the new regime Derby invested heavily in players in 2015/16,

spending £26.6 million. Manager Paul Clement was sacked by Morris

in February 2016 for not playing football “the Derby way”, and the club

missed out on promotion to the Premier League after being eliminated

in the play-offs by Hull City. On 28 March 2018 the club, via the official

website, published the following press release:

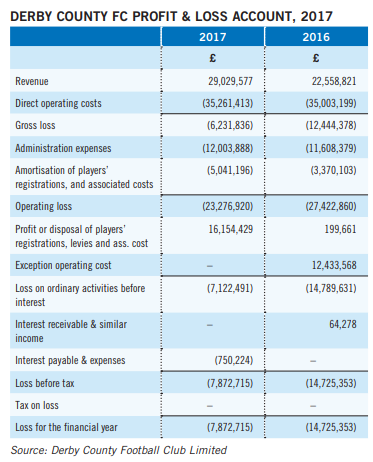

“Derby County have today announced their financial results for

2016/17 season. Reporting another record turnover and more strategic

investment on the playing side, operating functions and infrastructure of the club… The financial year 1 July 2016 to 30 June 2017 saw a best-ever Championship turnover (in non-parachute years) of £29m, up £6.4m on the previous year… The signing of players including Matej Vydra, David Nugent and Ikechi Anya were made during… the year… the sales of Jeff Hendrick, Lee Grant, Will Hughes and Tom Ince in this financial year contributed to a profit on player registrations of £16.2m…

Total staff costs across the Clun rose from £33.1m to £34.6m… The overall result was a loss of £7.9m in the financial year, compared to £14.7m in the previous year.”

The website did not, unlike the approach taken by other clubs, publish

the accounts themselves. The local media summarised the press release in an article and as the results seemed an improvement on the previous year, there seemed little to get excited about, so everyone lost interest quickly.

On 6 April 2018 the accounts of Derby County Football Club Limited were submitted to Companies House. When compared to the press release, a detailed analysis of the accounts revealed, as C&C Music Factory used to sign: “Things that make you go hmmm…”. The income total had indeed increased by £6.4 million (an impressive 29%) compared to the comparative figures for the previous year, and the wages figure by a far more moderate 4 per cent. On the face of things this looked as if the club had controlled costs well for the year.

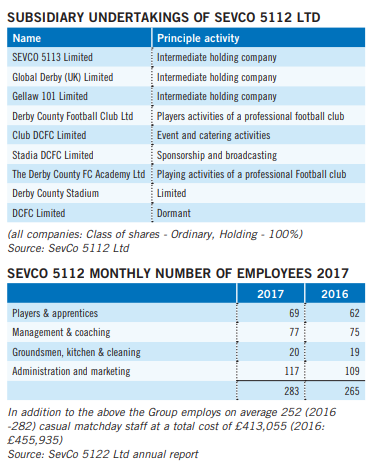

The wages note also revealed that the average number of employees

at the club had plummeted from 251 to 152, which seems strange given the club had not changed its activities in the year and so it seems difficult to justify a 40 per cent reduction in staffing levels. In the strategic report there was reference to companies called “Club DCFC Limited” and “Stadia DCFC Limited”, but no reference to how many, if any, jobs were transferred to these companies.

The profit and loss account did show a loss of £7.9 million for 2017 as

per the press release. The loss shown, however, was after players sales, which are volatile and unpredictable. The operating loss for Derby was over £23 million.

The Debry press release referred to the sale of Tom Ince and Will Hughes as being included in the profit on the sale in the year ended 30 June 2017. The excellent Hughes was sold on 24 June 2017 for an estimated £8m to Premier League Watford, a transaction perhaps accelerated to book a decent profit in the 2017 P&L account. Ince, however, was not sold by Derby until 5 July 2017.

Some would argue that the profit on the sale should therefore be delayed until the year ended 30 June 2018, although the accounting rules here are ambiguous.

Another figure that looked unusual was that of player amortisation,

which if you recall is the price of a transfer fee spread over the contract

life. Derby spent £51 million on players in 2016 and 2017 according to the accounts, yet the amortisation charge in 2017 was only £5.1 million. Until 2015, Derby’s accounting policy in respect of transfers was identical to that of all other clubs:

“Amounts paid to third parties for players’ registrations, Football League levies, agents’ commissions and compenstation for management and coaching staff are capitalised as intangible assets and amortised on a straight line basis over the period of the players’ or other employees’ contracts. Players’ registrations are written down for impairment when the carrying amount exceeds the amount recoverable through use or sale.” (Derby County FC)

But the club then changed its policy to the following:

“The costs associated with acquiring players’ registrations, inclusive

of EFL levies, or expanding their contracts, including agent fees, are

capitalised and amortised over the period of the respective players’

contracts after consideration of their residual values.” (Derby County FC)

It may not look a significant difference, but the key words are the

final ones “amortised over the period of the respective players’ contracts after consideration of their residual values.” Under such a policy a club has the opportunity to be creative with the figures to reduce the annual amortisation charge and so perhaps comply with FFP rules.

Consider the following: Fulchester Rovers signs a player for £12 million

on a four-year contract. Most clubs would therefore have an annual

depreciation charge of £3 million a year. If the club however allocates

a residual value of the player (residual value is the expected value of

the player at the end of the contract) of say £8 million, then the annual

amortisation charge falls to £1 million a year (£12m – £8m)/4). This would boost profit or reduce losses by £2 million in a year.

The amortisation charge as a proportion of the average cost of players

at the start and end of the year for 2016/17 shows Derby County on 11% at one end of the table and Barnsley at the other on 63%. A low figure means that amortisation is only a small fraction of the cost of the players and therefore has a relatively smaller impact on profits and losses. Derby County have by far the lowest amortisation percentage in the division for 2016/17.

Two years earlier, when their accounting policy was the same as for all other clubs, the figure was 29%, much closer to the divisional

average. If the figures are inverted it means that Derby are effectively

amortising their player signings over nine years (1/11%).

A look at the accounting rules on the topic (Financial Reporting

Standard FRS 102) per the Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales shows the following:

FRS 102.18.23 states that the residual value of an intangible asset must be nil unless either:

• A third party has committed to purchase the asset at the end of its

useful life, or

• There is an active market for the asset from which the residual value

can be determined and which is probable that such a market will be in

existence at the end of the asset’s useful life.

The rule would appear to suggest that Derby should not be using residual values for players income unless:

a. Derby have a third party committed to buying the player at the end

of his useful life. This sounds reasonable, but surely at the end of a

player’s contract he is entitled to a Bosman transfer and so there would

be no residual value, or

b. There is an active market for the asset. An active market is defined by accountants as “a market in which transactions for the asset take place with sufficient frequency and volume to provide pricing information on an ongoing basis”.

The problem here is that when dealing with individual footballers, they

are not being transferred on a frequent basis or at volume. There is, after all, as Derby fans occasionally sing, only one Bradley Johnson, and as such there is not a set price for his registration. A football registration is not the same as the value of a barrel of oil or a taxi licence for a city where the value of the asset is identical. It would therefore appear that Derby’s approach is inconsistent with the rules.

This doesn’t mean the club is wilfully doing something wrong, but the opportunity to reduce amortisation charges to comply with FFP limits is amplified.

So, what about the change in employee numbers? A few days after

Derby County Football Club Limited submitted its accounts for 2016/17,

SevCo 5112 Ltd did the same. SevCo 5112’s accounts were for the 10

months to 30 June 2017. This appears logical as it ties in with the football club’s year end. SevCo’s accounts showed that it now controlled a number of companies that had been set up to operate the different activities of the club.

This too is common in relation to the way that club activities are split up.

When it comes to wages and salaries, under accounting rules all subsidiary company results (where the parent owns more than 50%) are added to those of the parent. While it is unusual to separate out the academy team activities from those of the first team (as SevCo does), setting up a separate company to do this is perfectly legal and would give Derby’s owners a better indication of the cost of running the academy.

It therefore appears, rather than Derby employing fewer staff than

the previous year, as had been indicated by the Derby County Limited

accounts, employee numbers overall had in fact increased in 2016/17.

Wages cost did fall for SevCo 5112 by nearly 7 per cent to £33.2 million.

This, however, only covers a ten-month accounting period. If the figures are pro-rated upwards by multiplying by 12/10 it gives £39.8 million, an increase of 12 per cent over the previous year, much higher than the 4 per cent figure shown in the press release. While Derby and SevCo 5112’s activities are within the law, in terms of being open and transparent the approach is at best described as muddying the waters. Derby will no doubt claim there are legitimate business, operational and tax reasons for the new set up of companies within the group and if so, that is perfectly logical restructuring.

What rests less comfortably is the nature of the press release

at an earlier date that paints a rosier picture of the club finances than

might otherwise be the case. The club can argue that they are under no obligation to make the life of an analyst easy, but being obtuse only makes anyone with a curious mind want to look a bit closer, although the majority of fans won’t care an iota as long as the club is winning and compliant with FFP.

The following season Derby’s results also caused concerned as it

posted an initial loss before interest of just over £1 million, which seems very modest by Championship standards, but a couple of lines above the figure is £39.9 million of “profit on disposal of tangible assets”.

Further investigation reveals that this was the sale of the club’s stadium Pride Park, to another company controlled by the club owner, Mel Morris.

There is nothing illegal in such a transaction but without it the club may

have almost certainly exceeded allowable Profitability and Sustainability

loss limits and may have been subject to a points deduction the following season.

An understanding of the basics of a set of accounts is of benefit for

anyone who wants to analyse the finances of an individual club or division in a league. Some clubs produce excellent summaries of financial data, with Juventus perhaps producing the most detailed of any club in terms of information about players.

It is, however, concerning that too many clubs use creative accounting, legal loopholes, delaying tactics and sleight of hand when reporting their financial affairs, as this only reinforces the view held by many fans that some club owners are acting in their own interests rather than for long-term benefit of the fans and local community.

This is an extract from Kieran Maguire’s fantastic book ‘The Price of

£ootball’. To order a copy of Kieran’s book go to: https://www.agendapub.com/books/33/the-price-of-football

• Kieran Maguire is a Senior Teacher in Accountancy at the University

of Liverpool