June 2020

Richard Murphy explodes some myths about how many think fiscal policy will look in the ‘new normal’ economy.

Everyone keeps saying that nothing will be the same when

coronavirus is over. The claim assumes that we will get over coronavirus: I am not sure we will, but I will ignore that for now because whatever happens what I am quite sure of is that tax will not be the same. There are three reasons.

First, the amounts of tax that we will be expected to pay might change after coronavirus, but not necessarily as most people might expect.

Second, our logic about why we tax will I think change, because what we will have learned from this crisis, again in ways most people might not expect.

And third, we could end up with a quite different tax system as a consequence.

How much tax will we pay after coronavirus?

There is a widespread feeling that because the government is spending more as a result of coronavirus taxes are bound to rise as a result. I have good news on this: I think that is

exceptionally unlikely. Instead, if anything, I am expecting tax decreases over the next year or two.

That is because there is a very real risk that once furlough is over there might be up to eight million unemployed people in the UK. If that is the case then the overall level of demand in the economy will be suppressed. If any lesson was learned from the 1930s, when we last faced a problem of this scale, it is that to increase tax in this situation is to make the problem worse.

This is, of course, because taking tax from someone reduces their capacity to spend. And if we reduce the capacity to spend when the economy is already facing a massive downturn, we just make things worse.

So, right now do not expect any tax increases and instead anticipate cuts.

Do not, however, expect this to last forever. By the time the economy begins to recover (and one day it will) I think it likely that we will have realised that things like social care, the NHS, strong education systems, better funded public services, and much more, are still important to us, then at that time we will have to begin paying for them. I then expect taxes to rise. But that may well be some time off. And what I cannot stress strongly enough is that taxes will never have to increase to pay for the deficits that we are now incurring. That is because, quite literally, they are imposing no cost on us. This needs explanation.

What taxes really do

Most people think that tax pays for government services. That is not the case in countries like the UK. In practice, it has always been the case that the UK government has been funded by a mix of tax and borrowing, meaning that there was never a dependence upon tax alone. Those options have now been extended.

In addition to borrowing, government funding can now include both quantitative easing (QE), which now amounts to about £635 billion in the UK, or nearly 30% of total supposed UK government debt, and direct monetary funding (DMF) of government spending by the Bank of England, which simply means the government runs an overdraft with the bank it owns, and need not pay interest on it in effect, because the money comes straight back to it.

Both QE and DMF represent the government funding itself. What this means in practice is that the government’s own bank (the Bank of England) creates new loans to the government to fund its spending and never expects to have those loans repaid. And since, like all bank loans, those from the Bank of England to the government are made out of entirely new money created for this purpose tax is never involved in this process.

There is, incidentally nothing novel about this: no new bank loan ever recycles depositors’ funds now, which is a fact acknowledged by the Bank of England(1) in April 2014. And, despite all the claims that are often made that this will give rise to inflation of the type seen in the Weimar Republic and Zimbabwe, inflation has struggled to reach the 2% government target that has been set for the past few years.

In addition, given that governments around the world, plus the European Central Bank, are all doing this when they can, no one is at risk of exchange rate crises as a consequence.

What this does mean though is that tax does not need to fund the coronavirus crisis, just as government borrowing did not, because of quantitative easing, fund government deficit from

2010 to 2013, and there is absolutely no risk of inflation as a result.

Nor, come to that, will the cost of this borrowing, if interest is paid, be excessive: the UK government can borrow at less than 1% at present. This is a negligible interest cost, while because most borrowing is over quite long periods, when inflation is taken into account just 37p might, on average, be repaid for every £1 borrowed as long-term debt at present. In effect, those who are queueing up to lend to our government right now (and they are) will be paying for this crisis and taxpayers never will.

In that case, the role of tax is quite different from that which most people expect. The reality is that, as one of the members of the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee admitted(2) in April 2020, whenever the government spends the payment is not made out of tax revenue.

It is, instead, made out of money made available to the government by the Bank of England. The reason why tax is charged in that case is to reclaim that money from the economy to prevent excessive inflation arising. Tax does not, then, fund spending. Tax does instead cancel the inflation consequences of that spending.

This radical reappraisal of the role of tax in our economy is part of a school of economic thinking called modern monetary theory (MMT) that is rapidly gaining credibility, simply because governments are, as a matter of fact, subscribing to the patterns of behaviour that it describes.

But, as I have shown in my work as a professor of political economy, this gives rise to radical new way of thinking about tax(3).

New approaches to tax

For a start, this thinking suggests that equating government spending with ‘taxpayers’ money’

make little sense in this context.

It also shatters the myth that balanced budgets are necessary. In fact, it says that if inflation is too low (and that is now the tendency in the UK) then deficits should be run.

And what that implies is that governments can run deficits without having to apologise for doing so, which has been the pattern for so long. But perhaps most important of all is the fact that if tax is not funding the government then it assumes a different role in society, apart from just cancelling inflation.

Sources as apparently unlikely as the Financial Times have suggested this. They suggested in April this year(4) that the coronavirus crisis requires the reversal of the policy trends of the past four decades and a revamp of the UK’s social contract.

Among the ideas it promoted were greater equality and the taxation of wealth. Understanding how that might work requires a better understanding of how tax works now.

Working with Prof Andrew Baker of the University of Sheffield, I have developed a method for doing this called tax spillover analysis(5).

Using this, it is easy to see that the current UK tax system is far from socially neutral. Over £400 billion of tax reliefs and allowances are given away each year and 81% of UK wealth is held in heavily tax incentivised assets(6).

In addition, the UK’s system of allowances and reliefs has a substantial redistributive effect, subsidising the already wealthy. When, as the new understanding of banking that modern monetary theory delivers, and which the Bank of England has endorsed, makes clear that savings are not required to fund investment in the UK economy, the time has come to engage in a systematic evaluation and overhaul of the UK’s system of allowances and reliefs.

That is because these reliefs cost the government money and at the same time undermine tax’s anti-inflationary potential by interfering with the integrity of the spend and tax cycle, while providing little verifiable benefit in many cases. As a result we are suggesting radical redesign of the tax system, not to raise more tax (because it is not as yet clear that is needed) but to actually make the tax system fairer.

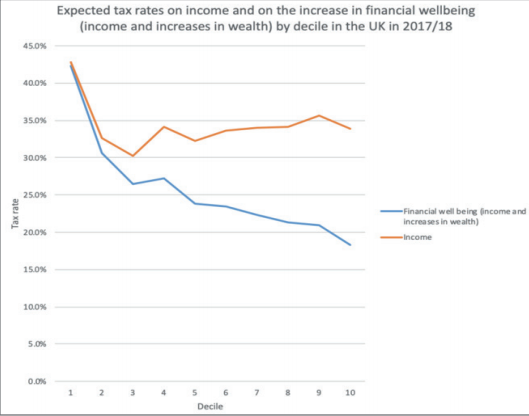

And that greater fairness is possible and probably necessary is apparent. When the combined value of income and increases in wealth – averaged over a seven-year period – are compared with the taxes paid on income and wealth in 2017/18 and the result is plotted by decile (which process simply splits taxpayers into ten groups of equal size, starting from the lowest income group and going up to the highest) this chart can be plotted(7):

The lowest earners in the UK have the highest effective tax rates, and the highest earners the lowest effective tax rates.

The Financial Times is right to call for wealth taxation and a radical overhaul of our tax system. And if those on low pay, who we clap each week because many of them are what we now call our essential workers, are to get a better deal as a result of their work on Covid-19 then their taxes need to fall and the wealthy might need to pay more. And for those in the middle? There is no reason to worry: it’s unlikely much will change there.

Tax should look different after coronavirus in that case. But not in the way most people expect.

In recent work, we created a framework for assessing ‘tax spillovers’ or the vulnerabilities and weaknesses within tax systems posed by the pursuit of tax competition. From a modern money theory perspective, such a system of evaluation can help to identify weaknesses that might impair a taxation system’s aggregate ‘cancellation function’ and suggest reforms to rectify that.

Such tools will be essential in the post Covid19 world, if governments are to assess whether their tax systems are delivering ‘cancellation’ effectively. The framework also enables a more precise appreciation of how specific reliefs can undermine the redistributive integrity of tax systems as a whole.

In the emerging Covid-19 economy, the challenge is to overhaul tax systems so that they are no longer weighted towards the wealthy, but redistribute towards those whose precariousness has been exposed by economic shut down, while becoming more effective in relieving potential

inflationary pressures. Government has both the spending and monetary levers to take the larger role in the economy demanded by the current emergency and called for by the Financial Times. But a lasting, more resilient social contract requires an accompanying rethink and reassessment of both the macroeconomic and social policy roles of tax. The qualified application of MMT to questions of tax reform and imbalances we offer provides a starting point for that.

• Richard Murphy is Professor of Practice in International Political Economy, City University, London

Bibliography:

3 http://www.paecon.net/PAEReview/issue89/Murphy89.pdf and https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/social-policy-and-society/firstview

4 https://www.ft.com/content/7eff769a-74dd-11ea-95fe-fcd274e920ca

5 https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/1758-5899.12655

6 https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/social-policy-and-society/firstview