February 2021

What is quantitative easing? PQ examines an increasingly popular

phenomenon that continues to divide the experts.

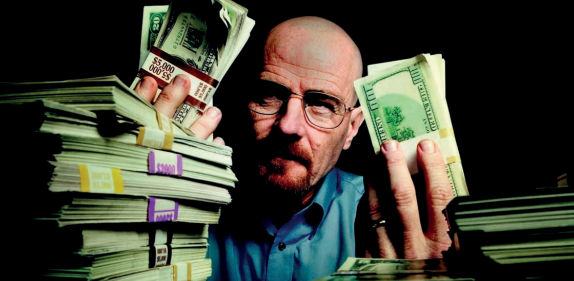

Quantitative easing (QE) is the creation of new money to facilitate an increase in spending and investment in the economy.

More specifically, a country’s central bank, in the UK’s case the Bank of England, creates money, usually in digital form, to buy government issued bonds from banks and other large investors, providing these institutions with increased amounts of highly liquid money.

In the UK, the first QE programme was introduced in 2009, and new programmes have been launched as the result of the eurozone debt crisis, Brexit referendum and, most recently, the coronavirus pandemic. The US, Japan and Eurozone countries have all used QE since 2009.

Why is quantative easing used?

To help you understand QE think of the economy as a machine, where money is the oil. A constant steady flow of the oil is necessary for smooth and efficient functioning.

Having an adequate money supply and low, positive and stable inflation is integral to a healthy UK economy. Often this is achieved by the Bank of England, the body responsible for controlling money supply and ensuring the UK’s inflation target is met, by changing the Bank of England Base Rate. Following the credit crisis of 2007-08, the Bank Rate was lowered from 5% to 0.5% in order to encourage economic activity by incentivising spending and investment.

However, a zero or negative low base interest rate limits monetary policy and can hurt economic activity. So, in times where monetary stimuli is required, but a reduction of base interest rate is constrained, the Bank of England turns to QE.

The positive implications of using QE is twofold:

• The creation of money to buy government issued bonds from banks and other large investors increases the demand on government bonds, which lowers the interest rates on those bonds. This reduces the interest rates offered on loans (importantly mortgages or business loans) as returns on government bonds are related to other interest rates in the economy. Therefore, QE allows the lowering of nominal interest rates (the interest rate which high streets banks charge and lend to businesses at) without changing the base interest rate, which makes borrowing and lending cheaper.

• A lack of a circular flow of money in the economy (remember, it is a machine) results from the lowering of propensity to spend, which occurs during economic hardship.

This results in a reduction of business income, increasing the likelihood of cost-cutting measures like reduced wages or even unemployment for staff, and the reduction of investment into profitable business ventures.

This in turn leads to a negative cycle in which spending, income, investment and economic activity all spiral downwards. The purchase of government bonds provides investment institutions with highly liquid forms of money, which enables firms to invest or lend if they so choose, injecting money into the economy, restarting the flow of money.

Simply put, QE makes borrowing and lending money cheaper, encouraging spending and investment, by influencing interest rates and increasing money supply in a controlled way. Some economists have claimed that the ‘QE experiment’ since 2008 has helped economic growth, kept wages higher and unemployment lower.

What are the dangers of QE?

Monetary policy constantly represents a money supply balancing act: too little and the economy gets stuck and can’t function; too much and it becomes flooded. There is the risk that QE results in an excess money supply, resulting in a devaluation of domestic currency, higher than desired inflation and even ‘stagflation’, an extremely damaging type of inflation that occurs under no economic growth.

Furthermore, the government and central bank cannot force firms to invest and lend, and inject the money into the economy. Therefore, QE can be seen as risky by some policy makers, with the desired outcomes not guaranteed.

In addition to these, QE represents a large expenditure package and so results in the increase of a fiscal budget deficit. This threatens the UK’s fiscal stability by increasing debt and loan interest repayments.

Lastly, due to the nature of QE, as well as the price of bonds, QE results in the increase in the price of shares and property. Although this makes those holding shares wealthier, it can be seen as regressive, hurting poor and younger members of society.

And because government bond prices are used to calculate future pension costs, as bond prices rise so the cost of providing future pensions rise. Firms are then obliged to make larger payment into their pension schemes, reducing investment. As a result, QE can and has led some pension schemes to close altogether.