August 2021

Sarah Ardiles explains all you really need to know about amortisation – how it works and how to apply it.

You have probably heard of the term ‘amortised cost’ in financial reporting. But what exactly is it and what gets measured at amortised cost? Let’s answer the second question first. Most financial liabilities (think loans, bonds, debentures) are measured on this basis.

Lease liabilities are effectively treated as financial liabilities and are also measured at amortised cost.

The basics

What is ‘amortised cost’ and how do we apply it? Well, as the name suggests, it is a cost-based measure. Let’s take a simple example: a loan.

Imagine you borrowed $20,000 and you must pay interest at 3% per year (in arrears) and the loan is repaid in three years’ time. Every year, there are two things happening to the size of your loan.

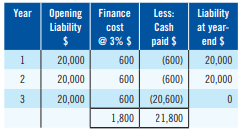

On the one hand, over time, interest accrues on the loan and your liability increases. On the other hand, with each cash repayment you make, your liability falls. In the first two years, the cash you pay is just the interest whereas in the third year, you pay both the interest plus the capital element of the loan (the amount you borrowed):

As you can see, the amount borrowed was $20,000 but the amount you repay (including the interest) is $21,800. So, you pay back $1,800 more than you borrowed and this ‘finance cost’ is charged to profit or loss each year at $600 (3% of $20,000). In other words, the cost of finance is spread (or amortised) over the term of the debt.

Additional finance costs

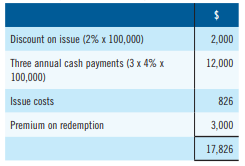

Let’s consider a more complicated scenario. A company issues 100,000 4% loan notes of $1 each. They are issued at a discount of 2% and the company incurs issue costs of $826. On redemption (in three years’ time), the $100,000 loan must be repaid, plus a premium of $3,000. How many costs of finance can you spot?

There are quite a few actually:

Why are the discount on issue ($2,000) and the premium on redemption ($3,000) considered costs of finance? Well, the company is borrowing $98,000 ($100,000 less 2%) and will have to repay $103,000 (par value of $100,000 plus $3,000). Therefore, it must pay back $5,000 more than it borrowed, and this expense is therefore a finance cost. The three annual payments of $4,000 are further costs the company suffers to service the debt, and the issue costs are also incurred because of raising the finance. In total, the company will incur $17,826 finance costs over three years which must be recognised in profit or loss over that period.

Recognising the finance cost

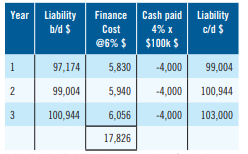

My next question is how do we spread that total finance cost to profit or loss? I would love to tell you that we simply divide the $17,826 into three and charge a third of it to profit each year. Unfortunately, life’s not that simple, and IFRS 9 has good reason to prohibit this method: over three years, the liability will rise from around $98,000 (in actual fact, it is $98,000 less the issue costs) to $103,000, so it’s only fair that the amount of interest charged each year should reflect the size of the outstanding liability – both will get bigger.

Thus, IFRS 9 requires that the annual finance cost be calculated by applying the loan’s effective interest rate to the outstanding liability. Any payments made are deducted from the liability. And this is all amortised cost is. The effective interest rate is a percentage which incorporates all the costs of finance: the higher the total cost of finance, the bigger this percentage will be. I have calculated that the effective interest rate for this loan is 6% (you will be given this in your exam so look out for it). Thus, over time the liability will look like this:

Initially, the liability is measured at fair value less transaction costs, i.e. net proceeds received ($98,000 less the issue costs of $826). This way, rather than expensing the issue costs in full on the date of issue, they are initially debited against the liability and get expensed over the three years – remember, they make up part of the 6% finance cost rate! Over time, the liability grows so that by the end of year three, just before repayment, it is $103,000 – the par value plus the premium, being exactly what is due for repayment.

In the first example, the only finance cost was the 3% interest on the loan, so 3% was the effective interest rate. Whereas in the second example, there were several finance costs which all get reflected in the 6% effective interest rate.

• Sarah Ardiles is freelance lecturer specialising in FR and SBR. Email sarahardiles@hotmail.com